Unit 5 • Lesson 8

The Cultural Landscape as a Tool For Learning

1.1 – The Cultural Landscape as a tool for Learning

Look around you. Scan the landscape for buildings, bridges, roads,plants, animals, people, a river, the sun and clouds. Feel the ground underfoot. Take a moment to study and reflect on everything you see. How do you perceive your surroundings? What do you think and feel about them?

Your personal reflections may help you realize that no matter where you are or what you do, you can’t escape being a living, interacting part of the landscape around you. When you use your mind and senses to ponder your relationships and interactions with other people, human structures, and the natural world, you are stepping into the realm of cultural ecology.

Cultural ecology studies people’s relationships with their environment and how they use their culture – their learned and shared behavior – to adapt to their world. In this sense, culture can be viewed as an adaptive system, a system that changes its behavior in response to its environment, in order to achieve a goal or objective.

Cultural ecology also studies how interactions between humans and their environment impact each other. Ultimately, it is human culture – what people have learned and how they utilize their knowledge – that determines our relationship with nature. Keep in mind that you are a part of that process. Whenever you interact in some way with your environment, other people, or other organisms living within a landscape, you are behaving in a way that relates to cultural ecology.

Cultural ecology occurs on landscapes, which are areas or territories that include water, plants, animals, geological features, and all the factors that created them. Landscapes are places where humans interact with these factors. People leave their mark on landscapes when they inhabit them, alter them, and adapt to them. Interactions between human systems and the natural systems in their environment create a cultural landscape that conveys information about these interactions and how they have influenced and changed both systems, and how humans have adapted to their environment.

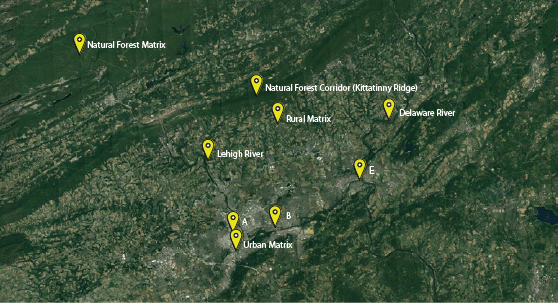

The Lehigh Valley is comprised of a variety of cultural landscapes. Cultural landscapes are formed over time by a succession of cultures and their interactions with the natural landscape. (Lance Leonhardt)

Cultural landscapes are a collection of natural ecosystems (rivers, forests, etc.) and human ecosystems (towns, cities, etc.). Key elements of a cultural landscape are physical geographic elements (Lehigh River, South Mountain); living land cover elements (vegetation patches); and human elements (infrastructure such as railroad tracks, buildings, and bridges). (Lance Leonhardt)

Cultural landscapes are everyday landscapes that surround us wherever we conduct our activities. The study of cultural ecology attempts to help us understand the relationships between people and nature as they are expressed or written in cultural landscapes. That is why cultural landscapes – born from interconnected human and natural activity – are key objects in the study of cultural ecology.

A landscape, when considered as an ecological level of organization, is an area of land comprised of interconnected, interacting ecosystems. A cultural landscape is formed by the activities of a succession of human ecosystems, whose cultures integrate technology with learned and shared behaviors in order to create economies and lifestyles that shape the natural landscape over time. Since human ecosystems involve interactions between people and their physical and living environment at all scales, the concept of a human ecosystem can be applied to a family, a neighborhood, a city, or a global community.

Therefore, as a collection of natural and human ecosystems, a cultural landscape includes 1) physical geographic elements, or landforms such as mountains and rivers, 2) living land cover elements, or vegetation, and 3) human elements, which include different human land cover elements such as physical forms of infrastructure (buildings, bridges, roads, etc.), and different land use functions, or ways in which humans utilize the land to their advantage. The natural landscape supplies the materials, or natural resources, for human use, and also sets limits on how human activity forms the cultural landscape. For example, the physical condition of the land, as well as its composition and shape, limit the type, size, and form of infrastructure that can be constructed at a particular location.

Modern cultural landscapes may contain remnant structures of past cultures called legacies such as the Weir covered bridge built in 1841 over Jordan Creek in Lehigh County. (Lance Leonhardt)

Cultural landscapes contain and express a historical record of human actions, especially settlement patterns and economic activity. Human actions transform the land and create new cultural landscapes over time that are superimposed, or layered, on the remnants, or legacies, of older cultural landscapes. As a cultural landscape evolves, its identity, as well as knowledge acquired by past cultures who inhabited the landscape, may remain or can become lost. The same can be said for physical remnants of the landscape’s material culture, its human artifacts. (A culture is a group of individuals – a society – who share and interact with a certain set of knowledge, beliefs, art, morals, laws, customs, or any other learned capabilities and behaviors.)

In order to adapt successfully to a landscape and its environmental challenges, people must be able to accurately recognize, or “read,” the factors that comprise a cultural landscape and then determine whether they are beneficial or non-beneficial to human existence. People also must be able to recognize changes that take place within a landscape over time, and understand why these changes take place. Perception and understanding of challenges and changes have always been the goals of people who want to live and survive in a landscape, and continue to derive and sustain prosperity from it.

A culture (society) that does not pay attention to environmental challenges and changes, or is unable to recognize them and fails to solve and adapt to their consequences, is likely to face adversity. That’s why it’s important for people to acquire knowledge and understand the relationship between themselves and their environment. (To expand on this thought, you will be asked later in this unit to read, analyze, and understand information on climate change, one of humanity’s most important current issues.)

A landscape’s components: To better derive meaning from a cultural landscape, let’s take a deeper look at a landscape’s components and how they interact and function as a whole within the context of their place and time. Remember, cultural landscapes result from continuous, long-term interaction between human actions (activities) and the natural environment, which includes topography, vegetation, bodies of water, and climate.

Human actions transform the landscape according to a system of rules that are guided by cultural and natural traits. Cultural traits include language, knowledge, beliefs, values, symbols, and food habits, among others. Natural traits include topography, climate, and available resources. Culturally determined rules lead to choices that produce the components of a particular cultural landscape that are associated with human actions. Nature’s laws, or rules, produce landscape components that are associated with natural processes. Two examples: Tectonic and erosional processes produce landscape components such as mountain and river system patterns. Climatic forces and other variables such as topographic characteristics, determine landscape vegetation patterns. These natural landscape components provide opportunities – and also set limits – to human components, or actions, that shape the cultural landscape.

Components can be tangible, or physically “touchable” forms such as buildings, roads, rivers, or mountains. Intangible, physically “untouchable” components have an abstract quality or attribute. Mental or cognitive processes including knowledge, skills, and beliefs are good examples. Functions (something’s purpose or use) are also intangible since they involve actions, processes, and transformations of energy that may not be physically touchable. In a human system, intangible components also can be economic processes: choices and decisions regarding what to select, buy, sell, and consume. In nature, intangibles can be processes or activities such as photosynthesis, erosion, natural selection, and climate, all of which take place but are not physically touchable.

Rules, which are also intangibles, allow or prohibit actions based on certain norms or standards, and lead to cultural landscapes characterized by different orders. An order has two aspects: 1) the tangible, physical arrangement and organization of landscape components, such as the interconnected pattern of natural and human-made structures; 2) intangible commands – rules – that determine how physical landscape components are ordered, organized, arranged, and used. These commands can come from nature (described by the scientific laws and principles behind natural processes), and from human laws and regulations that determine what, how, and where human-made structures can be constructed

Humans transform the natural landscape to create

cultural landscapes. Road construction involves

interactions between tangible components (physical composition and topography of the land, road-building materials, machines, workers) and intangible components (knowledge and skills of workers, rules and regulations, costs that guide the construction process). (Lance Leonhardt)

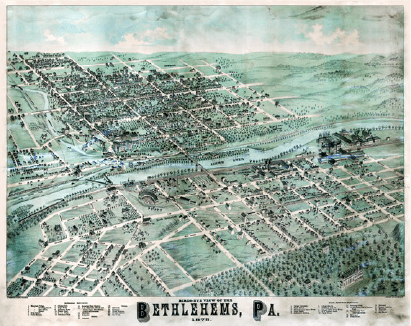

The physical placement, order, and development pattern of cultural landscapes are determined by the interaction between natural and human factors. Bethlehem was located near abundant water sources and on slightly elevated terrain. An orderly street grid plan, as shown in this 1873 city map, was implemented early in Bethlehem’s history. The grid plan created more intersections and increased connectivity between locations, making it easier for people to find their way. (Bethlehem Area Public Library)

Therefore, cultural landscapes are reflective of some sort of intangible idea, model, or plan originating in the human mind. These ideas and plans are brought into tangible, physical reality by applying a system of rules that determine choices. For example: How does a person accomplish work? What should the work include or not include? What should the work emphasize and how should it be organized? Choices like these are determined by considering the possibilities, constraints, and limits placed on the outcome – the cultural landscape and its uses – and also by the characteristics of the human and natural systems involved.

Consider the form of a cultural landscape such as a city. A city’s placement, order, and development are determined by interaction between natural rules and human rules, plans, and decisions. For example, the three largest Lehigh Valley cities of the 1700’s – Bethlehem, Easton, and Allentown – were founded following land purchases based on human rules – deeds, treaties, business deals – that designated the location of land open to settlement and what permissions were required to purchase the land.

Selection of the settlements’ original sites (now the cities’ historic districts) likely was based on favorable characteristics of the natural landscape. Slightly elevated terrain, for instance, was a preferred topography for building homes and commercial establishments. This type of terrain also made it easier to build infrastructure for transportation, beginning with simple roads for horses and stagecoaches. Having water sources nearby was important for drinking, cleansing purposes,

and economic production, since streams provided energy through water-wheel technology to power sawmills and grist mills. Water resources also could be used for simple irrigation of crop fields and orchards. Bethlehem was located near springs along Monocacy Creek and very close to the creek’s confluence with the Lehigh River. Easton was settled at the confluence of the Lehigh and Delaware rivers, in a low-lying area surrounded by hills. Allentown was situated near the Jordan and Little

Lehigh creeks and the Lehigh River.

The organization of the three cities’ streets was based on a planned human order, a basic grid pattern or grid plan, by which streets are built either parallel or at right angles to each other. Such a grid plan creates frequent intersections that facilitate pedestrian movement and make it easier to plan direct routes to desired locations. Streets set in a grid help with wayfinding, or the ways in which people orient themselves in physical space and navigate from place to place.

To summarize, a cultural landscape is an interwoven blend of form, function, meaning, and identity. Interrelationships and interactions between a cultural landscape’s tangible structural forms (streets, buildings, grid plan, etc.) and its intangible human components (experiences, knowledge, skills, rules for activity and function) give the landscape meaning and identity. People who interact with a particular cultural landscape by physically being inside it and viewing it should be able to perceive, or interpret, the landscape’s identity and meaning if they have a proper understanding of its forms and functions.

Classifying cultural landscapes: The integration of a cultural landscape’s form (physical structure) and function (use) determine its meaning and identify its landscape type and land-use category, or classification. Categories that identify land-use types depend on the definitions being used for classification. For example, a cultural landscape might be classified as “natural” when it is defined as having more natural elements and very few human elements and influence. Conversely, a landscape greatly altered by humans and largely covered by human elements might be classified as “human-made.”

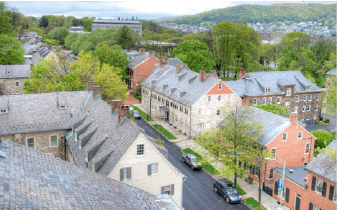

Moravian buildings dating to the 1700’s still line some of the original streets of Bethlehem, and give the cultural landscape that contains them an identity and meaning. Historical buildings and streets, as architectural forms, are legacies of the materials, construction skills, and traditions of past cultures, and can reveal how those cultures functioned in their environment. (Wikimedia Commons)

Cultural landscapes can be classified based on definitions of the structures and functions that create them. The term “natural” may apply to landscapes with more natural elements and fewer human elements and influences, such as a relatively large “natural vegetation patch” of trees along a “natural corridor” such as a river. The term ”human-made” may apply to landscapes greatly altered by humans and largely covered by human functional elements such as patches with “urban-residential”, “suburban-residential”, “commercial-industrial”, and “ agricultural” uses, and a “human-made corridor” such as a highway. The extent of view of this Google Earth image includes the cities of Allentown (A) , Bethlehem (B), and Easton (E) along the Lehigh River. (Google Earth)

Classification can be defined further by considering the amount of distinct areas of similar composition, or patch types, in a given landscape. Patches can include “living land cover” elements of natural vegetation such as you’d find in a park or natural preserve. Non-natural vegetative patches would be agricultural land planted in crops, or orchards and even tree nurseries. Patch areas comprised of human element types can include industrial, commercial, and residential buildings in urban, suburban, or rural areas. Corridor strips that function as conduits for the movement, or flow, of materials and people can be classified as natural (a river) or human-made (highways, canals, railroads). The Delaware & Lehigh National Heritage Corridor, or D&L Corridor, was a conduit for the movement, by canals and railroads, of anthracite coal and other natural resources that sparked the growth of industry in eastern Pennsylvania.

Specific combinations of patch and corridor types within a landscape’s matrix can be used to identify and provide meaning to different cultural landscapes. A landscape’s matrix is the portion of a particular landscape’s extent that covers the most overall area, and in which the landscape’s patches and corridors are embedded. The matrix surrounds its embedded patches and corridors, and so the matrix is typically a landscape’s most dominant, connected human land-use type, or natural background ecosystem type. For example, a city would have an urban matrix with embedded patches of vegetated parks and residential, industrial, and commercial land-use. An urban matrix also would include embedded natural and human corridors. A natural corridor could be a river; human-made corridors could be streets, highways, or railroads. In less populated rural areas a large, broad extent of natural forest stretching across a landscape would be the matrix if it surrounds and is embedded with a few human residential and commercial patches and road corridors.

A landscape’s matrix is the most dominant, connected human land-use type or natural background type of a landscape’s extent that covers the most overall area and embeds the landscape’s patches and corridors. Determining a landscape’s matrix type is a matter of viewing scale. This relatively expansive extent of view includes the cities of Allentown (A), Bethlehem (B), Easton (E), and the Lehigh and Delaware rivers, and reveals several matrix types. The patches and corridors comprising the three cities are embedded within an “urban matrix”. A “rural matrix” type embeds more dispersed residential and agricultural patches and surrounds the Kittatinny Ridge, the area’s most continuous “natural forest corridor.” A large forested area comprising state game lands and the Lehigh Gorge State Park surrounding the upper Lehigh River is a “natural forest matrix” type. (Google Earth)

The identity and meaning of a cultural landscape may change as human activity evolves through time and transforms the layers of physical forms that create the landscape. As a landscape and its population change, people interpret and understand the landscape differently depending on their level of knowledge, experience, and connection to it.

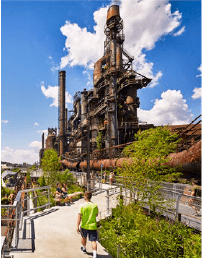

For example, when the Bethlehem Steel Company’s steel mill was first constructed along the Lehigh River, its infrastructure forms were designed for one function: produce steel. It was a cultural landscape built to make a product. To the men working there, the mill meant a job that provided a livelihood. The mill also provided the men with an identity: They were steel workers, which for many became a cultural and family tradition that was passed on from generation to generation.

Today, Bethlehem’s steel mills are closed, but the forms of the mills’ infrastructure remain and provide a backdrop for tourism. Newer structural layers have been added: shops, restaurants, a museum, a casino, walkways, roads, parking lots. Jobs and livelihoods are still available, though they are in the service sector and not heavy industry. For people who once worked at the steel mills, the landscape is a source of old memories. For tourists, the old steel plant and its forms are a source of curiosity, entertainment, and new memories.

The steel plant’s legacy structures (its remaining structures) are a source – an educational tool – for learning the history, culture, science, and economics of the once-burgeoning steel industry. Legacy layers preserve our cultural heritage, which includes tangible material objects such as architecture and artifacts, and intangibles such as a community’s valued traditions and history, which are inherited from past generations and shared today.

Cultural landscapes reflect and reveal how people have adapted to changing circumstances and conditions of their time. Interpreting the history of the Bethlehem Steel plant and other cultural landscapes in the D&L Corridor can help us understand an area’s cultural, economic, and natural heritage. Proper interpretation can provide meaningful insights that will help us plan sustainable, prosperous cultural landscapes of the future.

An overview of factors, forces and processes that shape cultural landscapes: We’ve arrived at a point in our understanding of cultural landscapes where it’s time to ask several questions that will help us gain further insight into the creation of today’s cultural landscapes.

• What are the factors, forces, and processes that create and change cultural landscapes?

• How have our cultural landscapes changed over the past 75 years (the course of a human lifetime), and why?

• How do these changes impact our ability to provide ourselves with livelihoods and well-being today and into the future?

• How can we use our learned and shared behaviors – our culture – to best adapt our cultural landscapes to a changing world?

Those four questions are central to understanding Unit 5. The overview that follows will help you understand what’s involved in creating today’s cultural landscapes. The overview is an introduction to the rest of the content in Lesson 1 and following lessons.

We have learned that cultural landscapes are created through relationships between humans and their environment, and that these relationships involve interactions that, over time, generate different and evolving layers of forms (also called material culture) across a landscape. The evolution of these forms represents phases of change, or

transformations that occur as people adapt to their environment in different ways, and at different times in history.

The site of the Bethlehem Steel Company’s steel mill is a cultural landscape with layers of legacy infrastructure (remnants of the mill) that preserve cultural heritage. New businesses and their infrastructure layers (museums, restaurants, entertainment centers) capitalize on this heritage for tourism, and educational and experiential opportunities. (asla.com)

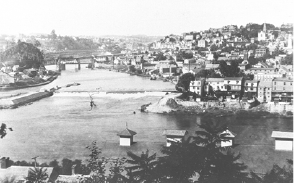

Two views of Easton, Northampton County, one from the late 1800’s, and a Google Earth image from 2018. These images illustrate changes to cultural landscapes that take place over time as layers of material culture (buildings, roads, bridges, dams) evolve in response to changing environmental, social, and economic circumstances and conditions. (National Canal Museum Archives, Google Earth)

Phases of change and their associated material forms can be seen as part of the adaptive cycles of various human ecosystem types such as a city or rural farm community. Human ecosystem types and their associated adaptive cycles have evolved and emerged over time in response to changing environmental, social, and economic circumstances and conditions. (See Section 5, page 51 for further explanation of human ecosystems and adaptive cycles.)

Phases of adaptive change involving people and the creation of cultural landscapes are driven by different natural forces and associated human forces. These forces are generated by three main factors: ecology, economics, and energy, the “3Es.” Interactions involving the 3Es, such as the combined use of fossil fuel energy, money, labor, machines, cement, and steel to build a dam across a river, are linked together by cultural aspects such as human thought, learning, behavior, and technology. Human and natural interactions involving the 3Es, and the forces for change they generate, are reflected in the creation and transformation of cultural landscapes, such as the transformation just cited that involves building a new dam across a free-flowing river.

The 3Es: Ecology represents the interconnected living (plants, animals) and non-living (rocks, water, etc.) environment, which we collectively call nature. Ecology includes natural ecosystems; biodiversity; natural landforms, features, and processes; and natural conditions such as climate. Ecology is the primary source of all energy and material resources used by humans and the economies they create.

Economics involves economies and adaptive strategies necessary for the production, management, and consumption of goods and services, as well as the technology and social organization necessary for human survival, well-being, and prosperity. Goods are tangible, physical objects that are produced, bought or sold. Services are intangible, non-physical products; activities that provide work for others, usually at a monetary rate of exchange.

The 3Es (energy, ecology, economics) are interconnected factors linked by human actions and technologies to create cultural landscapes. For example, a cement plant, as an industrial patch within an urban-suburban cultural landscape, integrates aspects of the 3Es in its structural and functional interactions with its surrounding environment. Ecology or nature provides the natural resources (limestone rock from a nearby quarry, water, oxygen, and fossil fuel energy) for industrial-economic cement production. Cement is then transported over human-made corridors (using fossil fuel energy) and sold for monetary profit to consumers in an economic market. Waste substances from production such as carbon dioxide gas not captured by pollution control devices are released into the surrounding ecological environment. (Google Earth)

Energy – the ability to do work – is required for the existence of ecology and economics. Energy is the key to all interactions and changes that take place in natural and human systems, adaptive cycles, the economy, and cultural landscapes. Different forms of energy – light, chemical, geologic, gravitational – drive natural processes such as climate, plate tectonics, erosion, and biological evolution, which form and shape the physical and ecological environments to which humans must

adapt. Solar/light energy is essential for agriculture, the primary method for human food production.

A fundamental part of understanding economies and the cultural landscapes they create is knowing how cultures and societies use energy and what forms of energy they use. Fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gas) have been the most important energy sources of modern human ecosystems in the United States since the 1840’s. Because fossil fuels have been so dominant, the ability to acquire and use them has been an important driving factor in the transformation of economic and technological processes and human-associated ecological changes in eastern Pennsylvania for nearly two centuries, and even longer in other parts of the world. Changes resulting from the use of fossil fuels during this time are reflected in the transformations of cultural landscapes.

The use of fossil fuels has led to unprecedented levels of technological advancement, wealth, and human well-being and prosperity for a substantial portion of the world’s human population. However, the expansive use of fossil fuels likely has led to the planet’s rapidly changing climate situation and the increasingly extreme weather events related to climate change. Climate change and associated environmental issues – sea rise, for example – impact Earth’s ability to support human and non-human life. Climate change is a situation that must be recognized, understood, and monitored in order for humans to properly adapt.

It’s important to emphasize that climate change has more potential to influence the development of present and future cultural landscapes – at all scales – than any other factor currently facing humanity. You will have the opportunity to study the causes, effects, and potential solutions to climate change in later lessons, in order to increase

your awareness and understanding of this issue. Learning, and making proper decisions based on what you learn, can enhance our capacity as a society to adapt to changing environmental conditions and circumstances. Adaptive learning is key to sustaining the prosperity of the society in which we live. How and why people adapt to their environment is central to the study of cultural ecology.

Global and local climate change and the increased potential for impacting cultural landscapes around us has occurred rapidly over the last few decades. In fact, we already may have changed the relatively stable climatic conditions of the Holocene Epoch, our current geological epoch, to such a degree that we have entered a potentially more turbulent new epoch called the Anthropocene, which we will discuss in later lessons. (In geochronology, an epoch is a subdivision of the geologic timescale that is longer than an age but shorter than a period. The Holocene Epoch is part of the Quaternary Period.)

“izations” as adaptive processes: In order to address and adapt to challenges from climate change and other environmental issues, it’s important to understand key connections and processes among the 3Es, connections and processes that the human mind, which generates culture, has linked together to create human ecosystems and cultural landscapes past and present. We will use specific terms – all with the suffix “ization” – to help denote and visualize these key adaptive processes.

As a suffix, “ization” signifies a process through which change initiates a transformation in the way human activities – labor, economic production, etc. – are accomplished and how people live. Changes in people’s activities, including their work and even their living and eating habits, are reflected in their cultural landscapes.

Different “ization” processes often interact. As a result, an existing “ization” process can be enhanced, or an entirely new “ization” process can be invented. Newly invented “izations” have occurred in sequential patterns over the past several centuries. The sequences, and the transformations they have fostered, can be chronologically related to several “ages” of human history.

To provide a better understanding, the following is a sequential listing of “ization” processes, some of which overlap, that have taken place over the past 250 years: mechanization…industrialization…urbanization…motorization…globalization…chemicalization…nuclearization… suburbanization…digitization-computerization…deindustrialization… revitalization/reurbanization.

All of these “izations” can be viewed as adaptive processes powered largely by fossil fuels and involving interactions among the 3Es. For the most part, these processes and interactions have resulted in forms, layers, and patterns of modern cultural landscapes, both locally and globally. For example, the cultural landscape of the

Bethlehem Steel mill, even though it is inactive today, can be associated historically with the “ization” processes of mechanization, industrialization, urbanization, globalization, deindustrialization, and revitalization.

During the past several centuries, “ization” processes have brought about the Industrial Age, Atomic Age, and the Digital Information Age. Interactions between the “izations” and the 3Es also have driven the ongoing Great Acceleration and entry into a possible new geologic time period, the Anthropocene. (The Great Acceleration, which began in the mid-20th century, refers to a continual surge in the global growth rate of a large range of human activities. Great Acceleration and

Anthropocene are terms that will be defined and described further in subsequent lessons.)

“izations” generated by interactions with the 3Es have produced two major economic transformations during the Industrial Age, which began in earnest in eastern Pennsylvania in the mid-1800’s. The first transformation, which started in the latter decades of the 19th century, was the migration of working people from farms to

factories, or, in cultural landscape terms, from rural to urban areas. This transformation involved mechanization and motorization, technologies necessary for the development of steam power, internal combustion engines, and electric motors. The transformation also included industrialization, urbanization, and globalization. All of these “izations” werepowered largely by fossil fuels.

The second major economic transformation, which began in the 1970’s and continues today, is the movement of many people’s employment from factories to offices, driven by the development of digitization/computerization technology. These technologies spurred the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) service transformation, which further enhanced the movement of workers living in cities to outlying suburban areas, a movement called suburbanization. Suburbanization began in the late 1940’s and intensified in the 1950’s with increased motorization, individual ownership of automobiles, and expanding highway and road systems. The “ization” processes

that made the second major economic transformation possible were powered by energy from fossil fuels.

The progression of the second economic transformation has led to increased globalization, deindustrialization, and, in some cases, a revitalization of cities and the reurbanization of their populations as people move back to urban areas from suburbs and other outlying areas. All these “izations,“ ages, and transformations have influenced the transition and formation of our cultural landscapes and the ecological state of our environment.